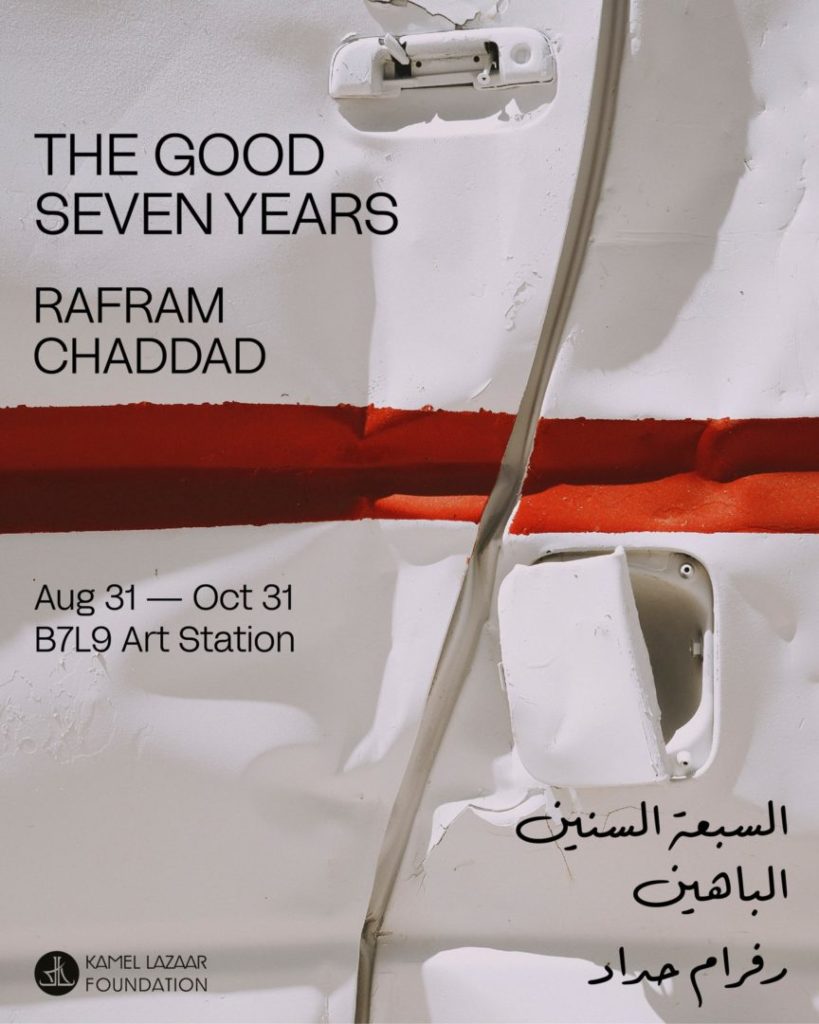

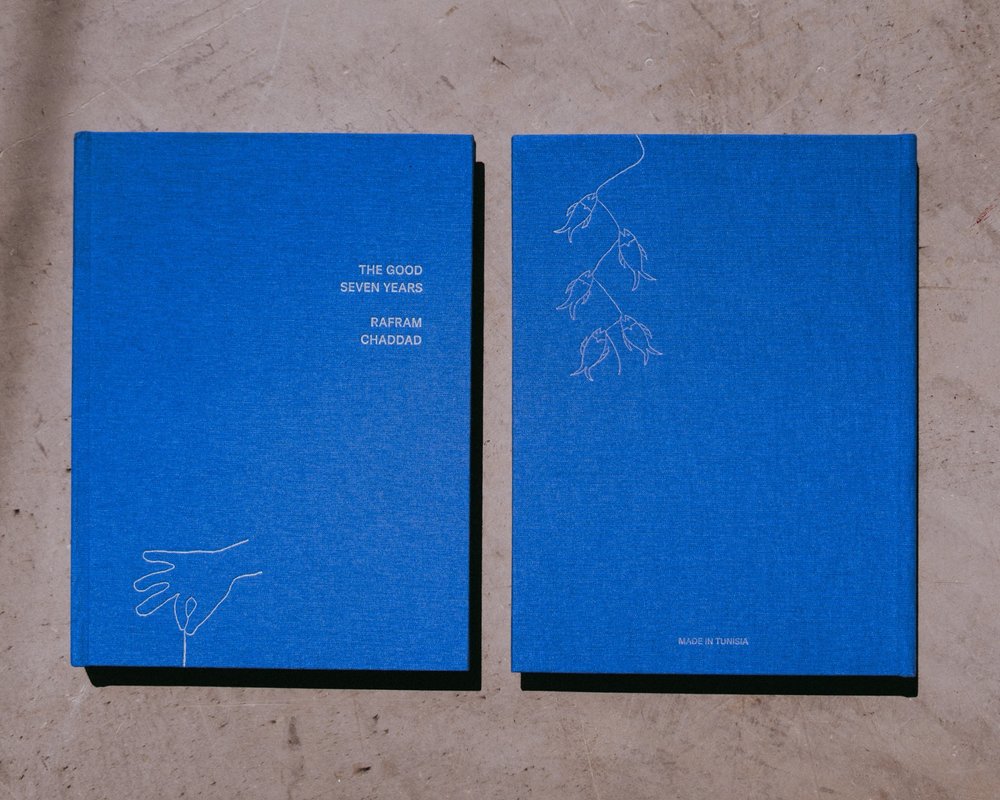

Born in Djerba into one of the oldest families in Hara Sghira (the “little Jewish quarter”) and raised in Jerusalem from the age of 2, Rafram Chaddad returned to Tunisia for the first time in 2004 and settled there in 2014. There, he has developed an artistic work on memory, the almost invisible presence of the country’s Jewish history – one of the oldest communities in the world – whose traces he endeavors to reanimate through interventions in the public space inspired by people, rites, objects and materials inspired by the vanished Tunisian Jewish world.

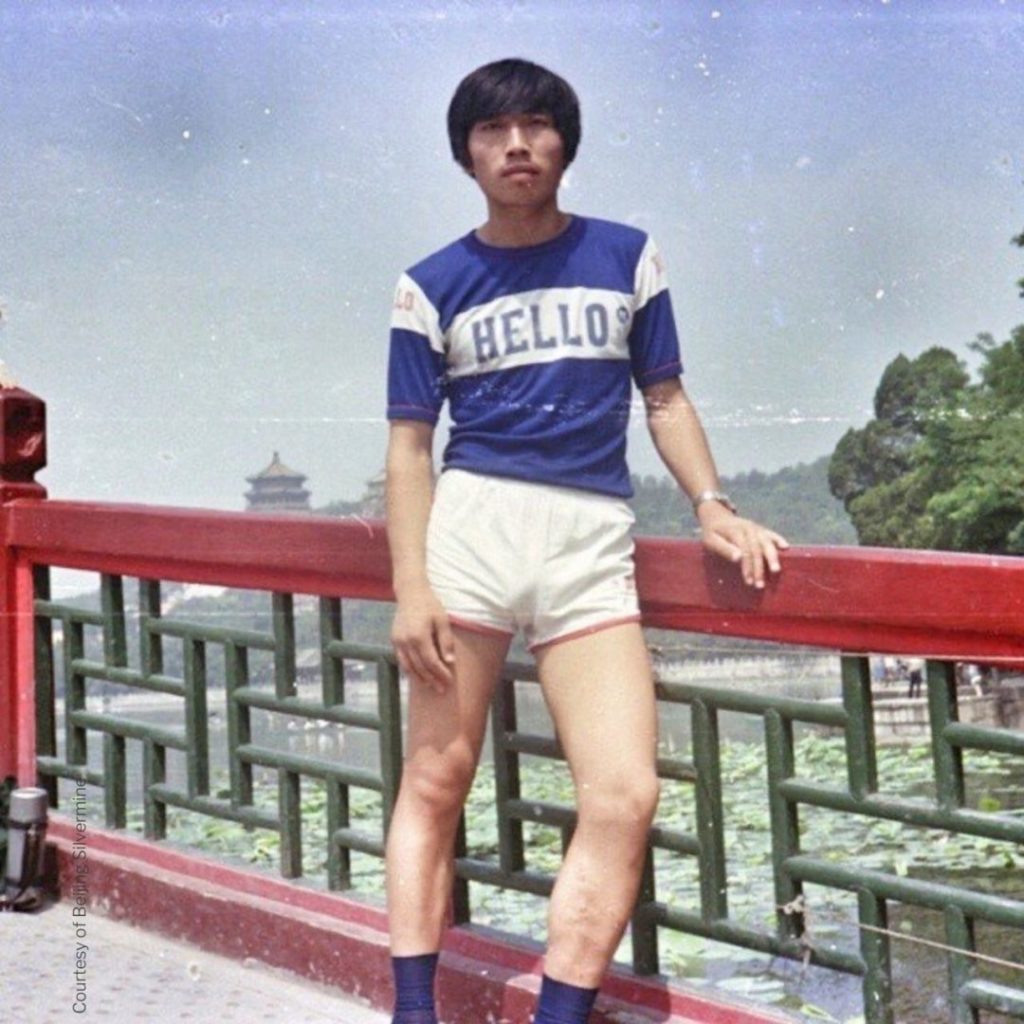

The Jewish population of North African countries, which numbered over 500,000 in the 1940s, has shrunk to less than 5,000 today. Yet the traces of this multi-millennia-old community’s presence remain, notably intangible, in the country’s music, cuisine and culture. It is estimated that between the 50s and 70s, more than 100,000 Tunisian Jews migrated to France and Israel. Many members of this diaspora never returned to Tunisia, but developed a nostalgia for their homeland as a lost paradise – a nostalgia familiar to those who live in exile. In this context, Rafram’s trajectory is disruptive, backward-looking, even transgressive (the previous generation claiming to have turned their backs on their Tunisian past to rebuild themselves elsewhere, in France or Israel, often in difficult ways).

In an essay from the book, scholar Yigal Shalom Nizri speaks of moving from a “metaspace outside the confines of time and space” to daily life in real space. This echoes the title “Comme à Tunis” given to the event at Grand Amour, and the experiences of the children and grandchildren of Tunisian Jewish immigrants, who have often lived in little Tunisias recreated in their grandparents’ apartments or in neighborhoods such as Paris’s Faubourg Montmartre, Belleville and Sarcelles – via cuisine, objects, rituals, beliefs and all the cultural signs perpetuated in exile. At the same time, Rafram’s gesture somehow unfreezes a time that was blocked at the moment of exile. His approach is anything but nostalgia: it’s not a question of reproducing the past, but of reactivating places, objects and rituals in a living, present way.

In this discussion, we talked about how Rafram’s art deals with the disappearance of the Jewish presence in Tunisia – and the impact of current events in the Middle East on his practice in Tunisia – but more broadly of how this artistic work evokes universal issues such as exile, migration, the fragility of borders and the mutability of identities.